Kategória: Research Blog

Forrás: https://digitalistudastar.ajtk.hu/en/research-blog/variations-on-geopolitics-flourishing-forests-and-world-war-two

Variations on geopolitics

Flourishing Forests and World War Two

Szerző: Wilhelm Benedek Tibor,

Megjelenés: 07/2017

Reading time: 10 minutes

The German school of geopolitics was established in the second half of the 19th century, when German economy was growing rapidly. From 1871, the united Germany was a country with great power ambitions. Its geopoliticians emphasized the significance of statehood and fostered the organic growth of nation states. Many of these ambitious concepts took hold in German politics and were used to legitimize its expansion plans. Then, as a consequence of the misery of two world wars, the German school of geopolitics lost its significance tremendously.

What happens to seedlings in big forests? Some wither and die in the shadows of other plants. They fall into oblivion. Other seedlings grow, flourish, and beat other plants in gaining the access to sunlight. Those victors shape the canopies of forests for decades. This allegoric introduction leads directly to one of the oldest schools in geopolitics, the German school of geopolitics.

Early German geopolitics is characterized by the paradigm that states function like organisms. The German geographer and ethnographer Friedrich Ratzel (1844–1904) was one of the founding fathers of the German school of geopolitics. With his works he contributed to the synthesis of politics and geography, emphasizing the role of territorial expansion and migration for the success of a nation. Ratzel’s viewpoint that states compete in a continuous struggle for life fits the metaphor of seedlings competing for sunlight. In this context, he describes the annexation of states as a natural procedure in the developmental cycle of states. In other words, seedlings become trees and expand their branches in order to receive as much sunlight as possible, while other trees suffer suppression.

Over the same period of time, the German liberal politician Friedrich Naumann (1860–1919) underlined the role of territory in the future of German geopolitics. In this regard, Naumann published a book on the German area of interest, called Mitteleuropa (Central Europe). In Naumann’s conception, Mitteleuropa is imagined as a federal central force under German hegemony. To unite this federal force, Naumann proposed fostering strong cultural and economic ties in Central Europe. In addition, he suggested strong military presence in the region to protect Mitteleuropa against other European countries and the Ottoman Empire. In reference to the forest example, Naumann’s emphasis on expanding Germany’s cultural, economic and military influence in Central Europe corresponds to the metaphor of those seedlings which grow strong roots and branches to compete with other trees for the sunlight.

German trees craving for sunlight

Source: Shutterstock

Swede Rudolf Kjellén (1864–1922) added another vital element to German geopolitics. The so-called “political activity” is embedded in the synthesis of the state and society. Moreover, political activity is divided into subcategories like Reich (realm), Volk (people), Haushalt (budget), Gesellschaft (society) and Regierung (government). If we understand territory, which has the same significance for Kjellén as for other geopoliticians of that time, as sunlight, political activity would represent nutrients. Nutrients in forests may not be as scarce as sunlight, however, water or carbon dioxide are still indispensable for the survival of the plants.

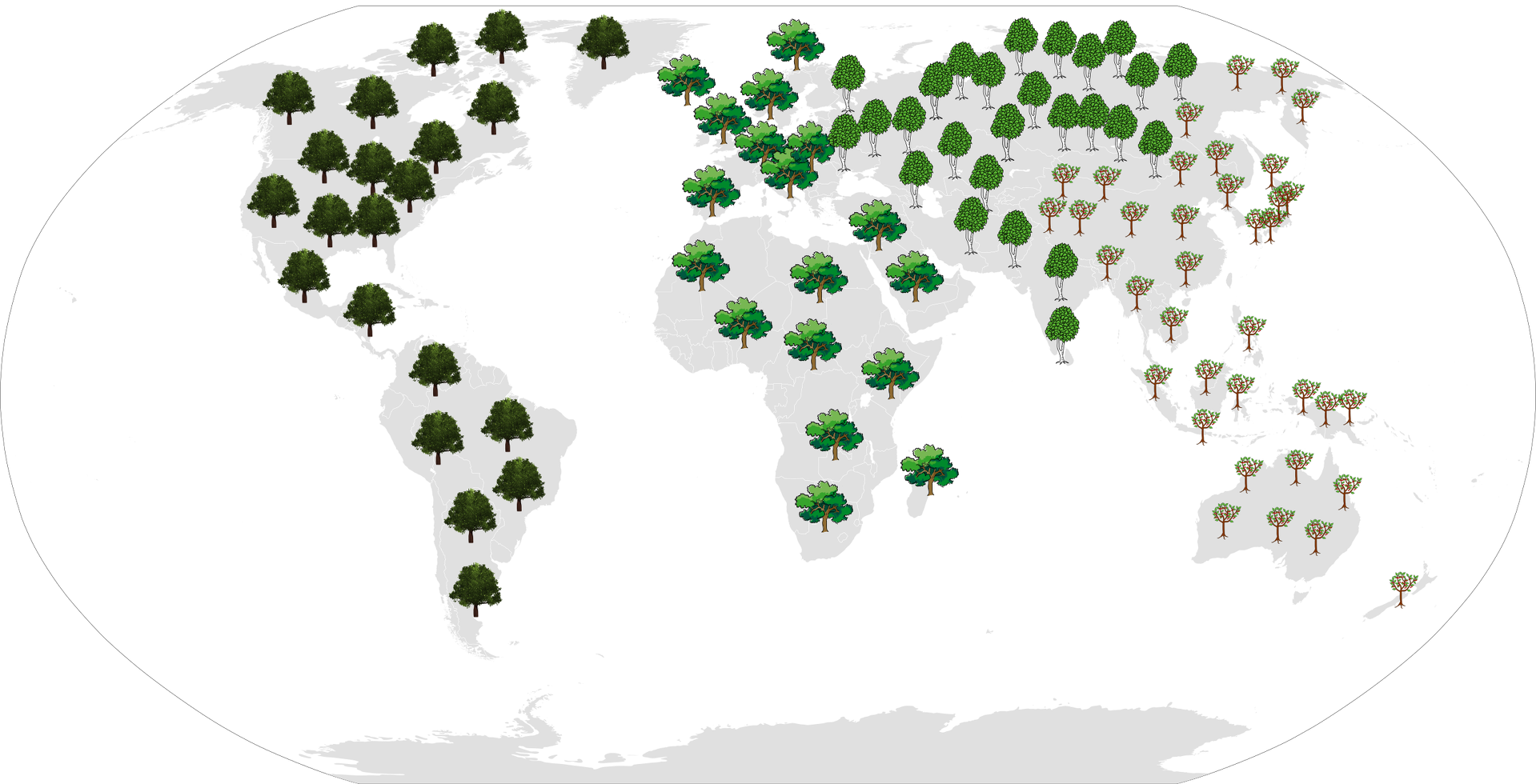

Another important note in context with German geopolitics is the concept of Lebensraum (living space). Initially introduced by Friedrich Ratzel, the geopolitician Karl Ernst Haushofer (1869–1946) developed the concept further. Like Ratzel’s approach, Haushofer’s theory links Lebensraum to territorial expansion. In Haushofer’s view, territorial expansion is automatically linked to the ambitions of expanding world powers. In this spirit, similarly to Anglo-Saxon geopoliticians, he divided the world into spheres, which he called Panideen (panideas). Haushofer’s Panideen (Pan-America, Pan-Eurafrica, Pan-Russia and the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity sphere) are meant to belong to certain areas of influence. In terms of trees, Pan-America under US influence would represent a hickory-dominated forest, Pan-Eurafrica under German influence would stand for an oak-dominated forest, Pan-Russia under Russian influence could be compared to a birch-dominated forest, and the Greater Asia Co-prosperity sphere under Japanese influence would represent a cherry blossom-dominated forest. As a tree species shapes the canopy of its forest, the respective state controls its Panidee. The ideas of German geopoliticians were absorbed by German politics and used for the legitimation of Germany’s colonialist interests in Africa and expansion plans in Eastern Europe in the time before and during the Second World War. A measurable contribution of this time was the scientific journal “Zeitschrift für Geopolitik”, in which authors like Karl Ernst Haushofer, Erich Obst, Hermann Lautersach and Otto Maull popularized the main concepts of German geopolitics.

Haushofer’s Panideen

Design by AJKC Research using the following elements: birch (by Etxeko), cherry blossom (by Spedona és Jean Paul Gibert), oak tree, hickory, world map.

Licensing: CC BY-SA 3.0

After the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, German geopolitics was associated with the great power plans of the German realm, and consequently lost its significance in society. In Eastern Germany, geopolitics was banned for the public. In Western Germany, the postwar period was dominated by two different paradigms. The Allies and especially the United States enforced the process of Denazifierung (denazification), which was aimed at democratic transition and the elimination of fascist and nationalist ideologies in the country. Accordingly, organic growth, folkish ideas and the concepts (popular with Germans) of hierarchical government contradicted the aforementioned aims. Therefore, the process of Denazifierung prohibited the smooth transition of the German geopolitical tradition. Nevertheless, certain geopoliticians in Western Germany attempted to rehabilitate German geopolitics or rather to distinguish scientific contributions from nationalist offshoots. For example, both the attempt of rehabilitation and the distinction of scientific and unscientific German geopolitics appeared in the works of the geographers Peter Schöller and Carl Troll.

Even though it is difficult to compare the cautious contributions of the post-World War 2 period to the classics of German geopolitics, jurist and political scientist Carl Schmitt (1888–1985) wrote, in addition to his main works on law and political science, about geopolitics as well. Schmitt concluded in his book Nomos der Erde (Nomos of the Earth) that the division of land is the matrix of human history, which can be exemplified by the paradigm that conquests, border demarcations, and the distribution of land are the roots of legislation. Moreover, Schmitt discussed the time period from 1648 to 1885 to describe virtues in the relations among European states. According to Schmitt, these virtues are based on equality, sovereignty, and the concept of mutual lawful enmity. This equal sovereignty and the conventional warfare of the time allowed for the easing of tensions in boundless places, such as colonies. Regarding the time after 1885, Schmitt described the collapse of the aforementioned time period by the separation of international law and territoriality. Schmitt argued that the division of global spaces would be crucial in the new nomos as well, but states would lose their significance as key actors and that new universalism would produce new spatial formations, which are strongly related to new opportunities like the domination of the sea and air. In other words, Schmitt describes how plants agree on space for their branches and how environmental conditions change the setting completely.

Although Carl Schmitt’s work is one of the most valuable contributions of German geopolitics, there have been other voices in the 1970s and 1980s questioning the absence of German geopolitics in scientific discourse. From German reunification until today, two main paradigms have dominated German discourse. On the one hand, the “Kontinuitäts-These” (continuity-thesis), which underlines Germany’s continuous successful role as a multilateral and cooperative civil power, and the “Normalisierungs-These’ (normalization-thesis), emphasizing the German role of a unified, densely populated central power and the necessity of a reorientation around German core interests in the country’s foreign policy. In summary, there are two different directions for the geopolitical future of Germany. Under these conditions, the rise of a valid scientific discourse with new paradigms seems to be only a question of time. However, it will be interesting to observe if and how new German geopoliticians adapt the ideas of the classical school of German geopolitics. Besides, it will be worth looking at how future German geopoliticians will evaluate the German foreign policy of the last century, in particular Germany’s integration to the West, its new East policy, international peace missions, and role in the European Union.

The next blog post will introduce the French school of geopolitics, which emphasizes the role of humans in geopolitics. Check our AJKC research blog next week to understand why French geopolitics needs German beer.

Get inspired:

Ratzel, Friedrich (1897) Politische Geographie. München und Leipzig: R. Oldenbourg.

Ratzel, Friedrich (1882–1891) Anthropogeographie: Die geographische Verbreitung des Menschen. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Naumann, Friedrich (1915) Mitteleuropa. Berlin: Reimer.

Haushofer, Karl Ernst (1931) Geopolitik der Panideen. Berlin: Zentral-Verlag.

Haushofer, Karl Ernst (1928) Bausteine zur Geopolitik. Berlin Grünewald: Kurt Vorwinckel Verlag.

Haushofer Karl Ernst (1927) Grenzen in ihrer geographischen und politischen Bedeutung. Berlin: Kurt Vowinckel Verlag.

Kjellén, Rudolf (1917) Der Staat als Lebensform. Leipzig: K. Hirzel.

Schöller, Peter (1957) Wege und Irrwege der politischen Geographie und Geopolitik. Erdkunde. 1957/1. 1–20.

Schmitt, Carl (1950) Der Nomos der Erde im Völkerrecht des Jus Publicum Europaeum. Köln: Greven Verlag.

Stürmer, Michael (1994) “Deutsche Interessen.” In: Deutschlands neue Außenpolitik, Vol. 1. Grundlangen. Kaiser Karl/Maull Hanns Wilhelm (Hrsg.). München: Grundlagen.