Kategória: Research Blog

Forrás: https://digitalistudastar.ajtk.hu/en/research-blog/variations-on-geopolitics-a-sleeping-dragon-awakens

Variations on geopolitics

A Sleeping Dragon Awakens

Szerző: Wilhelm Benedek Tibor,

Megjelenés: 08/2017

Reading time: 12 minutes

The Japanese school of geopolitics emerged in the 1920s and 1930s as a reaction to European—mainly German—contributions to the field. While some Japanese thinkers criticized many of the European contributions and questioned even its validity as a scientific branch, others saw the potential in the geopolitical way of thought to provide relevant insight into the international relations of its time. Japanese geopolitics represent a school unto itself in one of the most competitive spheres of power, Eastern Asia.

Imagine a giant serpent-like dragon lying about on his island and protecting with his eyes an incredibly valuable treasure. Just as the dragon reaches out to stroke his treasure with his giant claws, ships arrive and strangers begin to set foot on the top of it. This very moment is the birth of Japanese geopolitics.

The ships arriving at the dragon’s island are comparable to the attempts of European colonial powers like Great Britain, Russia, Germany, and France to expand their sphere of influence in East Asia. As a reaction to these attempts, Japan pooled its resources in the Southern Expansion Doctrine (Nanshin-ron) to expand in Southeast Asia and the Northern Expansion Doctrine (Hokushin-ron) in Manchuria and Siberia. Parallel to these activities, Japanese scholars discovered geopolitics as a tool to legitimize Japanese actions and develop coherent geopolitical plans for realizing Japanese aims. These Japanese activities in the early 20th century, resulting in several military conflicts and substantial scientific contributions, symbolize the awakening of the dozing dragon.

The first impulse of the Japanese dragon from a geopolitical perspective were Japanese reactions to German scientific articles on geopolitics in the 1920s. Certain terms originating from German geopolitics, like Haushofer’s Lebensraum (Seikatsuken), were introduced into political and geopolitical discourse and adjusted to the political situation of the country. Even though leading geographers of that time, such as Goro Ishibashi and Takuji Ogawa, questioned the peculiarity of geopolitics as a separate scientific branch, and Hikoichiro Sasaki argued that Germans would causally relate politics and land, others, like Saneshige Komaki, found out about the political and scientific potential of geopolitics and developed it further by, for example, adaptions of Tennoism, which represents a complex spiritual and social concept of worshipping the emperor (tenno).

Subsequently, such thinkers were often supported by governmental structures, which established think tanks and expert groups. One of these think tanks was the Showa Kenkyukai (Showa Research Association), which was a diverse group of intellectuals, serving Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe by gathering information for his reform plans. In addition, there were two main Japanese schools of geopolitics. The military and ministerial authorities funded the Kyoto School of Geopolitics (within the Imperial University of Kyoto), which was dominated by the teachings of Saneshige Komaki and his students, seeking Japan-based political concepts and geopolitical contributions. The Tokyo School of Geopolitics (within the Imperial University of Tokyo) was more diverse, which can be exemplified by the efforts of Hiroshi Sato, who introduced the socialist writings of Karl August Wittfogel to Japan, and Joji Ezawa, who adapted the German concept of reconstituting conventional human and economic geography with the methodology of natural science. Altogether, it can be said that geopolitics was relatively late and controversially introduced to Japan. However, overlaps between actual Japanese politics and geopolitical research are obvious and contributed to the development of Japanese geopolitics. In the following, this article introduces some of the Japanese researchers’ contributions to the field, explaining the gradual awakening of the Japanese dragon.

The Japanese dragon awakens

Design by AJKC Research using the following elements: Dragon (design by OpenClipart-Vectors), Asia 1870s Map (taken by James Monteith), SailingShip (design by Con-struct), Flag of German Empire (design by Jwnabd), Flag of Russian Empire (design by TRAJAN 117).

Licencing: CC BY-SA 3.0.

The profile of Masamichi Royama, who was one of the first political scientists of his country, is revealing, as he was a professor from the Imperial University of Tokyo and a contributor to the Showa Kenkyukai. In the 1930s Royama was well-known for his liberalism and supported cooperation in the region. He joined the geopolitical discourse to share his expertise and to realize his objectives. In this spirit, Royama criticized the idea of Japanese Asianism, which was based on a communal unity under Japanese leadership, connecting the peoples of Asia. With regard to Royama, it is important to note that, in his eyes, Asianism could easily promote protectionism and he demanded that the government regain control from the military. Furthermore, Royama criticized Chinese nationalism, because it would consequently weaken the Chinese economy. His third main paradigm was to establish an efficient system of global cooperation, as he thought that the existing League of Nations had failed. Masamichi Royama’s opinions can be contextualized with geography. Japan occupied Manchuria in 1931, which led to the afore-described Chinese antagonism, Western and international sanctions, and, consequently, the rise of Japanese Asianism. Royama recognized this conflict and advocated efficient regionalism in the region to overcome the Manchukuo case and foster cooperation. Accordingly, Royama’s contributions would enable people in East Asia to walk over the Japanese dragon’s giant paws and use his body as bridges for commerce.

Another pioneer of Japanese geopolitics was Saneshige Komaki. Komaki not only led a group of experts on different global regions at the Imperial University of Kyoto, but also constructed a framework for Japanese geopolitics in the 1940s. History played a particular role in his work as a source from which to derive Japanese geopolitical traditions—e.g. the practice of Japanese isolationist policy from the Tokugawa period (17th century–19th century). In addition to this historical approach, Komaki integrated a spiritual component inspired by Tennoism into Japanese geopolitics. In contrast to Western individualism, Komaki intended to combine the Kodo spirit (the way of politics as performed by the godlike Japanese Emperor/Tenno) with geopolitics. By legitimizing Japan’s unique role in international relations and its different world view, he attempted to overcome the popular geopolitics of the time, which according to him were Eurocentric and only worked to maintain the Western status quo in world politics. Thus, his overall concept would allow the creation of an ideal world, where people from all over could live under one emperor (Hakko-ichiu). In this case, Saneshige Komaki used existing concepts from Japanese history, culture, and spiritual tradition to integrate them into his own concept of Japanese geopolitics. In this spirit, Komaki’s dragon would use, strengthened by new geopolitical ideas, his scaled tail to create big waves to push the arriving ships away then stretch its muscles and stand up.

Royama’s and Komaki’s contributions were so far compared to physical movements of the Japanese dragon. However, Joji Ezawa recognized an interdisciplinary problem in geopolitics, which can be illustrated with taking a deep breath before waking up. Ezawa did not focus on the Western impact on geopolitics like Komaki, but on the distinction of geopolitics and political geography. In this light, Ezawa correlated geopolitics with humanities and political geography with natural sciences. By doing so, he ascertained that geopolitics allows one to analyze the meaning of geography as an expression of the human spirit. In other words, geographical areas receive their value from human beings. According to Ezawa, the task of geopolitics would be to describe geography by classification and in consideration of meaning, which is given by humans. The afore-mentioned deep breath before waking up can be contextualized with the pleasant comfort of the sleeping dragon. This pleasant comfort is in the case of Ezawa resembles to the approaches of political geography, which do not recognize human impacts on geography and treat space as a pure variable of natural sciences. By neglecting the importance of the description of the causality between nature and human beings and by analyzing the role of humans in the creation of meaning in geography, Ezawa recommends that the giant Japanese dragon take a deep breath and become aware of what human impacts mean for geopolitics. For the elaboration of these ideas, former Haushofer translator Joji Ezawa took up Johann Gottfried Herder’s concept of meaning and harmony in a god-made environment by replacing the facilitator god with reasonability of human beings.

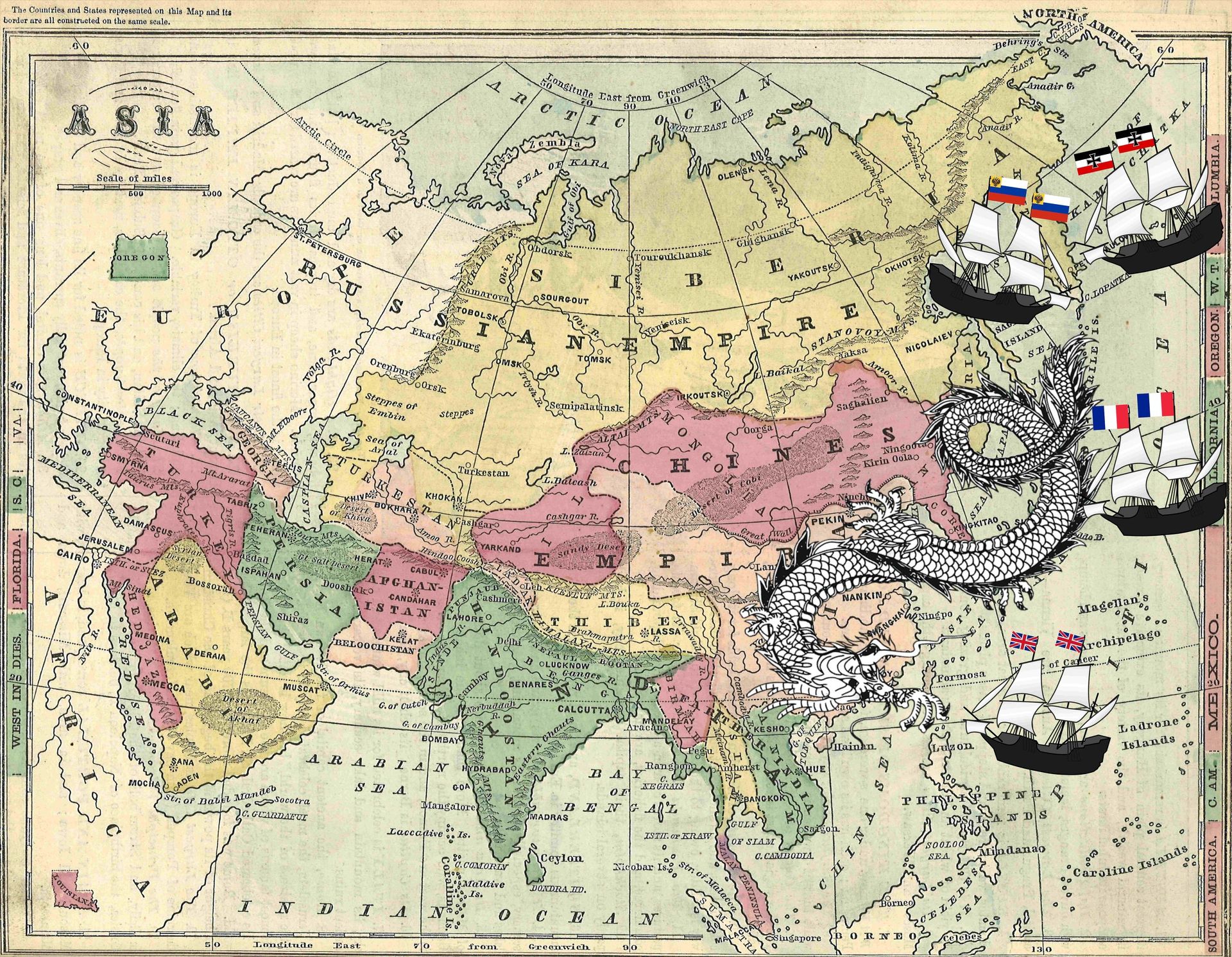

Area of Japanese puppet states during WWII

Source: Wikipedia

In order to classify the listed contributions between the two World Wars, it is necessary to give a short introduction of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (Dai Toa Kyoeiken), which covered Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia and parts of Oceania. The policy was announced in 1940 and was based on the ideas of the New Order in East Asia (Toa Shinchitsujo) for Northeast Asia from 1938. The initiator of this doctrine, Fumimaro Konoe, who was mentioned earlier in this article, formulated three main principles addressed to the anti-Japanese Kuomintang government in China. First, Japan will destroy the government if it keeps up its anti-Japanese and pro-communist attitude. Second, Japanese Tennoism and Japan’s uniqueness needs to be emphasized. Third, Western imperialism in East Asia needs to be reprocessed. These concrete governmental plans do not strictly represent the results of Japanese geopolitics but the common spirit therein, which is the independence from Western countries as represented, among others, by Royama’s regionalism and Komaki’s symbiosis of Japanese spiritual tradition and geopolitics. Finally, the image of the awakening Japanese dragon can be demonstrated on the one hand by the substantial contributions in a relatively short time frame between the two World Wars and, on the other hand, by the state’s support for this discipline.

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, the most important geopolitical figures resigned their offices and continued their work in other newly-established institutions. Geopolitics as a scientific branch was rejected and the academic discourse in this field was reduced to the republishing of critics of geopolitics like Keishi Ohara, criticizing the ideological character of geopolitics. Overall, Japanese academics after the Second World War did not elaborate a well-grounded critique, nor did they establish an alternative approach. Even though the dragon of Japanese geopolitics laid down to sleep again, some geopoliticians contributed to the Japanese economic miracle with their knowledge on regional studies via the Institute of Developing Economy (founded in 1962) especially in the context of economic relations with developing countries. However, whether the Japanese dragon of geopolitics is roused again depends to a large degree on the way Japan copes with its past, because the Japan’s role in East Asia and its alliance to Nazi Germany in World War II cannot completely explained without considering its geopolitics.

The next blog post will introduce you to the challenger of classical geopolitics, the so-called critical school. Check AJKC’s research blog next week and you will find out what thinking critically has to do with video games.

Get inspired:

Ezawa, Joji (1938) Keizai chirigaku no kisoriron, sizen/gijyutsu/keizai. Nanko-sha: Tokyo. Ezawa, Joji (1942) Kokuho chiseigaku no kihongainen. Chiseigaku 1(2), 77–86.

Ezawa Joji (1942) Chiseigaku gairon. Nihonhyoron-sha: Tokyo.

Komaki Saneshige (1942) Zoku-nihonchiseigaku. Hakuyo-sha:Tokyo.

Ohara Keishi (1936) Geopolitik no hatten to sono gendaiteki kadai. Shiso 211, 391–404.

Royama Masamichi (1933) Nihon seiji dokoron. Koyo-syoin: Tokyo.

Royama Masamichi (1938) Toa kyodotai no riron. Kaizo 1938 (11) 6–27.

Royama Masamichi (1941) Toa to sekai. Kaizo-sha: Tokyo.

Sasaki Hikoichiro (1927) Geopolitik to economic geography. Chirigaku-byoron 3(4), 99–101.