Kategória: Research Blog

Forrás: https://digitalistudastar.ajtk.hu/en/research-blog/the-western-balkans-and-the-year-2025

The Western Balkans and the year 2025

The Path to EU Accession for the WB6

Szerző: Dianna Horvát,

Megjelenés: 11/2018

Reading time: 7 minutes

“If we want more stability in our neighbourhood, then we must also maintain a credible enlargement perspective for the Western Balkans,” European Commission President Jean-Claude said in his State of the Union address in 2017, adding that “It is clear that there will be no further enlargement during the mandate of this Commission and this Parliament. No candidate is ready.” The speech provoked different reactions in the region, as well as the European Commission’s adoption of the document enlargement perspective for the Western Balkan countries at the beginning of 2018. Since then, we have often heard that 2025 is the year of the next EU accession.

States of western Balkan waiting for the European Union membership

Source: Shutterstock

Since the last—seventh—EU Enlargement in 2013, when Croatia joined the Union, five countries have been candidates for future membership: Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey. Out of these five, if we look at the Western Balkan candidates, Serbia and Montenegro have started accession negotiations, and managed to open chapters of the acquis by now. Albania and Macedonia are still waiting for the beginning of the accession talks, whilst Bosnia and Herzegovina signed a Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SSA) in 2008, and Kosovo in 2015, and they are both potential candidates. For all of them, there is still a lot to be done on their EU path. In the Commission’s Western Balkans strategy, six flagship initiatives are mentioned which target specific areas of common interest that need to be further developed: rule of law, security and migration, socio-economic development, transport and energy connectivity, digital agenda, and reconciliation and good neighbourly relations. Concrete actions in these areas are expected to happen between 2018 and 2020. The level of development of the WB6 in these areas is different, but there are some country-specific issues that also wait in line to be solved.

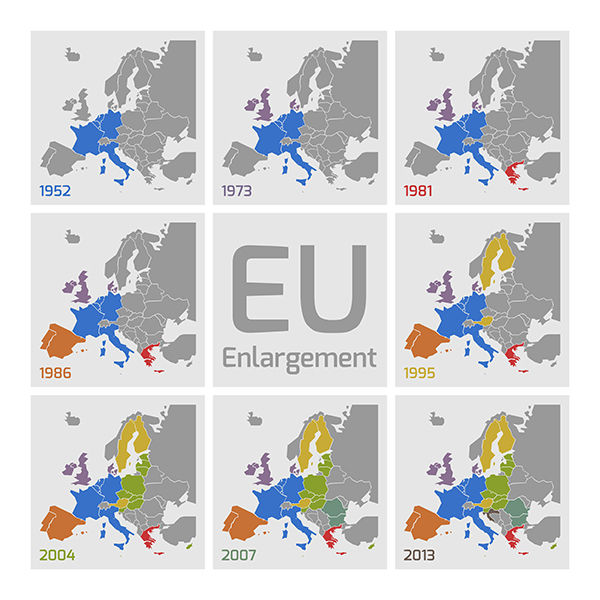

EU enlargements

Source: Shutterstock

The most well-known open questions are the Belgrade–Pristina dialogue, an ongoing, EU-facilitated negotiation since 2011, and the almost three-decade-long Skopje–Athens name dispute, which has started to give concrete results pointing towards reconciliation this year. Nevertheless, there are also other less-known bilateral disputes in the area, such as the border demarcation between Serbia and Bosnia and Hercegovina, or the border dispute that Croatia has with all of its neighbours expect Hungary. The whole region is beset with different issues, and even countries already in the EU cannot escape them. There is, for example, the Croatia–Slovenia unresolved border dispute regarding the Gulf of Piran, which has been straining relations between the parties since the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991.

A clear statement made by many EU officials is that, before the next enlargement, first the internal disputes among the candidate countries should be solved. There is also a realistic fear by some EU member states that this process of reconciliation will not happen in the near future. Therefore, it is not a coincidence that the Commission’s WB enlargement perspective states that “special arrangements and irrevocable commitments must also be put in place to ensure that new Member States are not in a position to block the accession of other Western Balkan candidates.” Something similar happened most recently in 2016, when Croatia firstly blocked, then eventually gave a green light to the opening of Chapter 26 (education and culture) for Serbia.

“Exporting stability rather than importing instability,” says Commissioner for Enlargement Johannes Hahn regarding his enlargement principle

Source: Shutterstock

The date of 2025 as the accession for some of the WB6 countries—the frontrunners being Montenegro with 31, and Serbia with 14 chapters opened out of a total of 35—is seen differently in the Union and in the region. As the Executive Director of the European Fund for the Balkans, Hedvig Morvai, said during the 2018 Belgrade Security Forum: “The date 2025 was never serious, let’s forget it. The region is not delivering reforms and the EU is not ready to change the approach to the region.” Somewhat more optimistic is Commissioner for Enlargement Johannes Hahn who explained that 2025 is an indicative date for Serbia and Montenegro, which is realistic but also very ambitious.

However, not everyone in the EU shares this opinion, one of them being French President Emmanuel Macron who stressed that he was not in favour of moving toward enlargement before having all the necessary certainty and before having made a real reform to allow a better functioning of the European Union. Paris’ point of view regarding the next enlargement was made clear when in June this year France, along with the Netherlands, postponed the beginning of the membership talks with Macedonia and Albania—the new date of the accession negotiations is June 2019, but a feeling of “broken promises” has since been lingering in the air.

The civil sector has spoken about the topic as well. The European Movement in Serbia and its partners from the region had defined twelve proposals on “how to re-energize the (EU enlargement) process,” which were published by the Belgrade Security Forum. Among the proposals is the alteration of the accession negotiations methodology, devoting more funds to the enlargement to the Western Balkans, and extending the benefits of its internal market to the region prior to accession as much as possible.

Whether the proposals are realistic, and whether the EU will take them into consideration is yet to be seen. Will the relationship between the EU and the WB6 countries be a carrot and stick game in the future? That will firstly be seen after the anticipated Skopje–Athens name solution, which is expected to happen in early 2019. As Commissioner Hahn stated “My enlargement principle is exporting stability rather than importing instability.”