Kategória: Research Blog

Forrás: https://digitalistudastar.ajtk.hu/en/research-blog/power-transition-models-in-central-asia

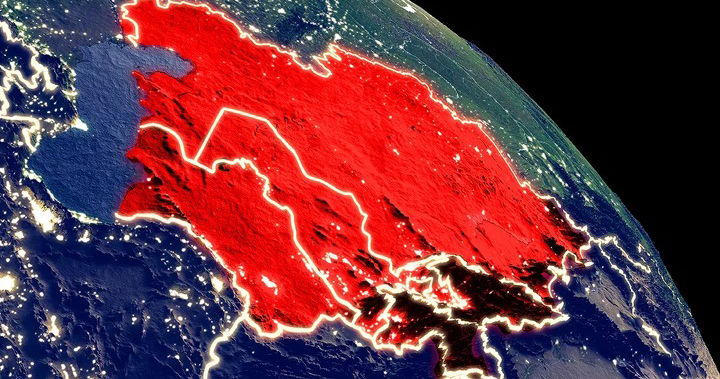

Power Transition Models in Central Asia

Lessons Learned and Future Prospects

Szerző: Arzuu Sheranova,

Megjelenés: 09/2019

Reading time: 7 minutes

Central Asia has recently seen a number of power transitions, while other local leaders are paving the way for a smooth and safe changeover. From our today’s post, you can find out what general conclusions are to be drawn from the different attempts of local strongmen to hand their power over while trying to ensure their personal and their family’s security.

In August 2019, Central Asia witnessed the violent detention of the former Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev (in power between 2011 and 2017) in Koi-Tash with the participation of two thousand policemen. Atambayev is the first ex-President in Kyrgyzstan (Roza Otunbayeva was interim President between 2010 and 2011) and Central Asia who voluntarily resigned right after his term limit had come into force, leaving the office to his friend and party fellow, Sooronbay Jeenbekov (incumbent since 2017). Shortly after, in 2018, the relationship between the two former friends began to worsen, and Atambayev had to face several accusations of corruption and the illegal release of a criminal, Aziz Batukaev. The charges led up to the revocation of his presidential immunity by the Parliament of Kyrgyzstan and his forced detention by security forces.

Atambayev followed a “Russian model of power transition” that proved to be successful in Russia at least once, if not twice, during the Putin–Medvedev tandem’s transition plan. Putting a similar transition model into action, Atambayev hoped to stay in power even after leaving his post through his influence over Jeenbekov and guarantee his political decisions, personnel appointments, and the safety of his family members and possessions. After the People’s April Revolution in 2010, the country became a parliamentary democracy. According to the Constitution of 2010, the President’s powers decreased fundamentally, setting the limit to a one-term office in six years. Additionally, according to the 2016 amendments to the Kyrgyz Constitution, the prime minister was given more authority and power. Atambayev hoped to return to big politics after the 2020 parliamentary elections by being elected first as an MP and, then, as a prime minister.

The former Kyrgyz President, Almazbek Atambayev in 2011

Source: Shutterstock

The transition of power in Central Asia has always been a worrisome matter for post-Communist ruling regimes. Since the fall of Communism, the region has only had a few “democratic” power transitions. The unexpected death of the Uzbek and the Turkmen presidents and the lack of the presidents’ well-planned power transitions disturbed the families of both Islam Karimov and Saparmyrat Nyýazow (in power in 1990–2016 and 1991–2006, respectively) with persecution and immigration. To avoid a similar fate, earlier this year, the Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbaev (in power between 1991 and 2019) has effected a transition of power to his loyal successor Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. However, in Kazakhstan, there was only a partial transfer of power because Nazarbaev still holds several high-ranking positions.

In Tajikistan, President Emomali Rahmon is preparing his elder son, Rustam Rahmon for replacing him. Rustam Rahmon became the Mayor of Dushanbe in 2017 and has since been accompanying his father during domestic events and affairs. In addition, earlier, in 2015, Emomali Rahmon introduced a Law “On the founder of peace and national cohesion—the leader of the nation” that guarantees Rahmon a lifetime immunity and safety after his presidency.

Likewise, the current President of Turkmenistan Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow (incumbent since 2007) is training his son, Serdar Berdimuhamedow, to succeed to him. At present, Serdar, publicly known in Turkmenistan as the “son of the nation,” is the governor of one of the provinces to the south of the country. The junior Berdimuhamedow accompanies his father on his international trips and sit in for him during important international events with an increasing frequency.

Contrastingly, in Uzbekistan, the relatively young and ambitious Shavkat Mirziyoyev (incumbent since 2016) is not yet bothered preparing an heir. Currently, he is busier with positioning himself as a new type of leader contrasted to Karimov. However, Mirziyoyev, along with other ruling Presidents in the region, was an attentive observer of recent events in Kyrgyzstan.

Shavkat Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s first official visit to Russia since his inauguration as the President of Kazakhstan on 20 March 2019

Source: kremlin.ru, licence: CC BY 4.0

The “Kyrgyz model of power transition” taught to Central Asian presidents in power that it was difficult to plan and implement a “proper” transition. It also revealed that power transitions in the post-Communist region were risky and unpredictable. To Kyrgyzstan, this pattern conveys the following messages:

- Kyrgyzstan is not ready for a parliamentary system of governance. The executive and legislative branches of power remained under the control of the President. Although the new Constitution guarantees future prime ministers more authority, presidents continue to preponderate. Correspondingly, the Parliament of the Kyrgyz Republic remains under the influence of the President.

- Regional clans’ role in politics persists. When selecting Jeenbekov as his successor, Atambaev took into account the regional tribal factor too. Jeenbekov, as a representative of the southern clans, was a good choice for him to counterweigh the popular competitor at the time, Omurbek Babanov, a representative of the northern clans.

- Political parties have weak political ideology and stay leader-centred. During Atambaev’s dispute with Jeenbekov, the Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan, the party in power, was split into two. Pro-Jeenbekov party members initiated a movement called “Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan without Atambaev” and could re-register the party in favour of Jeenbekov, although it was originally founded by Atambaev back in 1993. In the 2020 parliamentary elections, Jeenbekov’s team will run with a new political party affiliated with Jeenbekov in order to have a party of their own.

Meanwhile, in a broader sense, the following lessons can be drawn from the Kyrgyz pattern of transition regarding the entire Central Asian region:

- In Central Asia, a final word comes after the Kremlin’s consent. The Kyrgyz example demonstrated the influence of Russian leaders in relations between previous and current presidents. Both Jeenbekov and Atambaev sought for Russia’s support to secure his position in this conflict. The present outcome did not lack Russian involvement either.

- Power transition is partial. Other presidents would also consider a partial power transition following the “successful” Kazakh model by keeping security forces under the control of ex-presidents. Today, Nazarbaev’s transition plan seems to be solid and stable at the very least if not successful.

- The Russian model of power transition is risky. Events that happened in Kyrgyzstan showed that this option might pose hazards to Central Asian rulers.

- A khan-type model of power transition is a reality in several authoritarian regimes in Central Asia. As opposed to the Russian model and the unsuccessful Kyrgyz model, this might be a more favourable arrangement for some Central Asian rulers. Turkmen, Tajik, and, most likely, Uzbek strongmen are already looking forward implementing it by preparing their children to come to power after their terms.

Whatever model of transition will CA leaders implement later, this topic will remain an issue for them unless they can find other safe and suitable models.