Kategória: Research Blog

Forrás: https://digitalistudastar.ajtk.hu/en/research-blog/poland-will-be-either-great-again-or-none-at-all

“Poland will be either great again, or none at all”

The Morawiecki plan as imagined superweapon

Szerző: Roland Menyes,

Megjelenés: 05/2017

Reading time: 15 minutes

The Polish government intends to revive the country’s slowing economy through the implementation of a rather ambitious initiative. Their plan, which was named after the incumbent development minister, holds the promise of substantially alleviating the problems which have plagued Poland since decades and dragging it out of the so called middle-income trap by creating a stable basis for future innovations. Can the most populous member of the V4 group write a new success story?

Background

As far as macroeconomic indicators are concerned, Poland’s recent past seems to be glorious. A consistently adopted shock therapy at the start of the transition period put the country on a sustainable development path. After an early recession, which befell to various extent all the members of the dissolved Eastern Bloc that embarked on the path from communism to capitalism, growth returned and became a stable trait of the Polish economy. As a result, the country has more than doubled its GDP per capita level since 1989 and it has even overcome Hungary recently, which was not only much richer, but also started with far more advantageous conditions at the times of the regime change. In spite of this impressive performance, the Polish government thinks a new impetus is needed. To understand why, it is expedient to put the accomplishments of the last quarter-of-a-century into a wider context.

Respective GDP development in the Visegrad Group since 1989: economies to drift apart

Source: Central European Financial Observer

In terms of aggregate growth, Poland is miles ahead of other members of the V4 group. Not even Slovakia, which, as an allusion to the emerging powerhouses of the Far East, came to be nicknamed the Tatra’s Tiger, was able to perform that well, whereas the figures for both the Czech Republic and Hungary turn out to be more modest at best (see Chart 1). The situation is rather different, however, if we choose the average GDP per capita in the EU as the basis of comparison. In this case, both the Czech and the Slovak Republic are ahead of Poland (85%, 77% and 69%, respectively), which barely overtakes Hungary (68%).

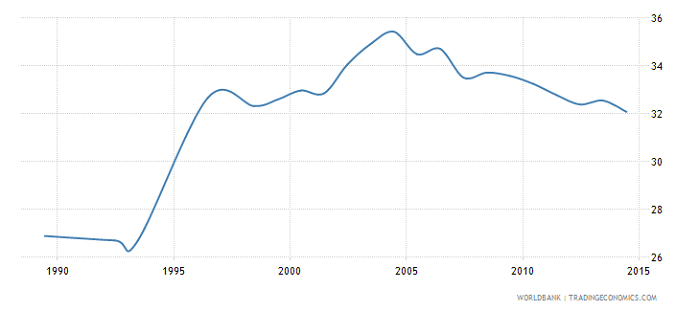

The strikingly good evaluation, presented in the first line of the paragraph, also hides serious domestic controversies. The neoliberal reforms’ course, which started in the early ‘90s and continued to form the backbone of the Polish economic policy in the ensuing decades – regardless of substantial political changes – produced serious side-effects. Belying the mainstream adage, which served as an exoneration for the hard-line reformers, the tide failed to lift all the boots, and neither the state nor the market provided adequate solutions for those who were unlucky enough not to share the fruits of progress. In time, rising social inequalities (see Chart 2) and salient intra- and interregional disparities became as characteristic features of the Polish way as the often-envied figures which gave evidence of an imposing economic take-off.

Chart 2: The change of income inequality in Poland from the beginning of the transition: a social rollercoaster of the wrong kind

Source: Trading Economics

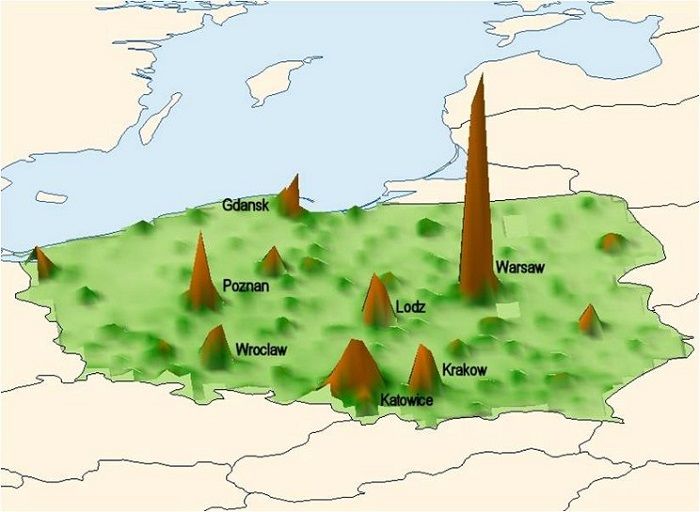

Owing to the curious twists and turns of history, there was nothing new either in the East–West developmental divide or in the economic concentration of the Warsaw region (see Picture 1). A rapidly widening income gap along with a galloping unemployment rate, which started to threaten with societal disintegration, was, however, an entirely new phenomenon. After more than four decades of communism, which produced at least some egality in poverty with only the nomenclature emerging as a modestly abundant class, the first experiences about the forces that capitalism can unleash caused a sobering shock.

Economic activity in Poland: either great or none at all

Source: voxeau.org

Considering this, it is quite a surprise that the country that takes pride in having been the cradle of the first independent trade union behind the Iron Curtain (Solidarność), undertook so little to prevent workers from falling victims to a lopsided development, after the former system, despised also for its hypocrisy, had crumbled. Without delving into a deeper analysis regarding the reasons, however, it is important to mention that the discussed problems which were partly inherited, party self-made, have lingered on under the surface and have grown serious enough over the years to thwart further progress. The incumbent government was neither the first to recognize this nor the only one to concoct brave ideas on the matter. Their current plan, nevertheless, merits attention on account of its ambition and coherency.

The Morawiecki plan in details

The Responsible Development Plan, as it is officially titled, consists of four main chapters. The first one identifies the problems Poland has to combat, the second lists the goals for the future, the third names the foundations on which development can be achieved, and the forth sets milestones for 2020. As to the problems – the so-called traps –, five are mentioned. First, the “middle income trap” refers both to the country’s position in international comparison and to the high disparities in revenues across society. To highlight only the most characteristic features: with the GDP per capita amounting to 45% of that of the USA, salaries are only third of those earned in developed countries, while two thirds of the Poles earn less than the national average (4000 zł ~ 1060 USD per month). Second, the “lack of balance trap” marks the country’s dependence on foreign entities. The symptoms here include a high level of debt payment crossing the borders each year (almost PLN 100 billion in 2016) as well as the fact that foreign firms are responsible for half of the entire industrial production and two-thirds of the Polish export. Third, the “average product trap” lies in the low level of domestic innovation: merely 13% of the LMEs undertake pertinent activities against 31% in the EU. Overall, less than 1% of the GDP is spent on R&D which explains why only 5% of the exports originate from high-tech sectors. Fourth, the “demographic trap” involves a low birth rate which caused that the number of Poles in working age started to decline in 2016 with no hope for the trend to change anytime soon. Finally, the “trap of weak institutions” jointly refers to phenomena like the meagre coordination of public policies, the swiftly altering regulatory environment, and the all too pervasive tax-dodging loopholes.

Mateusz Morawiecki, engineering a new Poland

Source: fot. PAP/Maciej Kulczyński

In the plan, the identification of the above traps is followed by a short elaboration of the strategic objectives which include the creation of a strong and effective state, the improvement of the quality of life, and the reinforcement of the role Polish capital and Polish enterprises play in the domestic economy.

Of course, the biggest question is how these goals can be achieved. According to the government, the solution must be based on the five pillars: firstly, reindustrialization with the concentration of resources in competitive branches and specialization of regions; secondly, support for innovative companies with the articulated aim of nurturing “national champions”; thirdly, the creation of a new legal and institutional background in order to achieve a higher saving rate along with the establishment of a massive development fund; fourthly, continuous support for export; and fifthly, supporting regional development in order to lessen the existing discrepancies both on intra- and interregional level.

As a testimony to their self-confidence, the authors set bold objectives for 2020. They predict that due to the implemented measures within 3 years, the Polish GDP per capita will reach 79% of the EU average and the share of R&D spending within the GDP will be 2.5 times higher than currently.

Professional evaluation and criticism

As soon as the plan went public, it came under professional scrutiny. Economic experts acknowledged that the problem analysis in the plan is competent, whereas they criticized assumptions that were either not precise enough or too generous. Moreover, apart from the criticism expressed regarding the feasibility of the proposed measures, while a historically rooted antagonism towards an overstretching state also resurfaced. To be sure, after decades spent under central control, suspicion is justified, but it is at any rate curious that little less than thirty years was not enough for the democratic state to achieve a much higher level of trust in its competency than its predecessor possessed. Thus, even though the authors aimed at striking a balance between state and market, the plan was viewed by many as the embodiment of a dangerous and unproductive interventionism which would only further elevate the risk of the already pervasive and growth-stifling corruption.

Reflecting the reservations, neither the intention of the government to earmark key sectors for development nor the mind-blowing accumulation of resources or the establishment of oversized bureaucratic bodies found much approval. Only the reindustrialization project resonated well among experts since it is in line with the unfolding processes in Europe. The production of complex goods with more added value has been gaining momentum anyway as the latest import/export figures also attest: 2015 was the first year for the balance of trade to swing into the positive realm. Other numbers, however, bode less well for the future. Both the additional rise in public debt and a scale-down in the field of investments due to insecurity in the regulatory environment cast doubt on the government’s ability to act consequently.

On one hand, the government reiterated its wish to reduce Poland’s dependency from foreign resources and entities. On the other, however, the lion’s share of the planned investment fund, is expected to come from abroad – in light of the country’s real financial possibilities a hardly surprising option. To shed light on the hard facts, it is worth mentioning that according to some calculations, without foreign investment, the Polish GDP would barely surpass that of Ukraine. Such considerations led to the plan’s feasibility being questioned on a purely theoretical basis. As the argument goes, since only a few countries have ever succeeded in joining the club of the most developed, the middle income trap, the so symptomatic feature of the periphery, from which Poland hopes to break out one day, may be purely a sham.

Conclusion

Is, therefore, the plan condemned to remain an outburst of patriotism based on wishful thinking, as its most pessimistic critics claim? The answer is far from clear. At any rate, it certainly does not pay enough attention to one of the most deeply rooted inhibitors of growth, namely to the state of the society. In this regard, the current proposal does not differ significantly from previous ones—in spite of the eloquent slogans the PiS is trying to conceal this fact with. Current acts of the government also raise doubts as to its understanding of the significance of this problem. Weakening or dismantling democratic institutions runs counter to lofty economic objectives, because the insecurity such steps necessarily bring forth keeps not only foreign investors at bay but undermines effective societal cooperation, too. As development theories came to recognize, the infrastructure of trust and a high level of social capital are crucial for economic development. Until these factors are not taken appropriate (practical) account of, a catch-up with the richer Western neighbours seems to be a dream slightly too daring.

Opening pic by Radio Maryja