Kategória: Research Blog

Forrás: https://digitalistudastar.ajtk.hu/en/research-blog/natural-gas-as-a-bridge-to-a-low-carbon-eu-society

Natural Gas as a bridge to a low-carbon EU Society

Szerző: Mihály Kálóczy,

Megjelenés: 02/2018

Reading time: 12 minutes

Almost all developed countries aspiring to use as much renewables as they can have to face the demand for a flexible backup energy resource. Natural gas would sound like a good solution for several reasons. However, natural gas fields are highly concentrated, so the abundancy of this resource at first sight is misleading – it cannot solve everyone’s problem. The three main regions where it can be found is North America (shale gas), Russia, and the Middle East (primarily Qatar and Iran). Considering energy needs, environmental, economic and political conditions, in some way or other, the EU must decide which option to choose.

First, the constraints:

- Natural gas is indeed the least carbon-intensive fossil fuel, but it cannot be an ultimate tool in the progress towards a low-carbon society until the storage or the conversion of carbon-dioxide is solved.

- Moreover, it is a hindrance in terms of the goals regarding greenhouse gas emissions.

- Extension and improvement of renewables in the Member States’ energy mix implies flexible backup technologies (such as hydroelectric power plants and gas-fired power stations).

- More member states (e.g. Ukraine, the Baltics) in the European Union have a relationship with Russia that is uncertain and full of tension.

- Many member states depend on natural gas: In the EU-28, dependency was 69.3% in 2015, up from 67.4% in 2014. Finland, the Baltics, etc. import the gas from Russia, but they are looking for alternate supply sources.

- The EU considers nuclear energy as a decarbonisation option, but most of the market (Member States) would prefer not to rely on it.

- The European Union cannot order a member state to change its energy resources or policy.

In terms of the big picture, this is not a question for the EU only: Almost every developed country aspiring to use renewables as much as they can has to face it. Globally, natural gas fields are highly concentrated, so the abundancy of this resource at first sight is misleading. The three main regions where it can be found is North America (shale gas), Russia, and the Middle East (primarily Qatar and Iran).

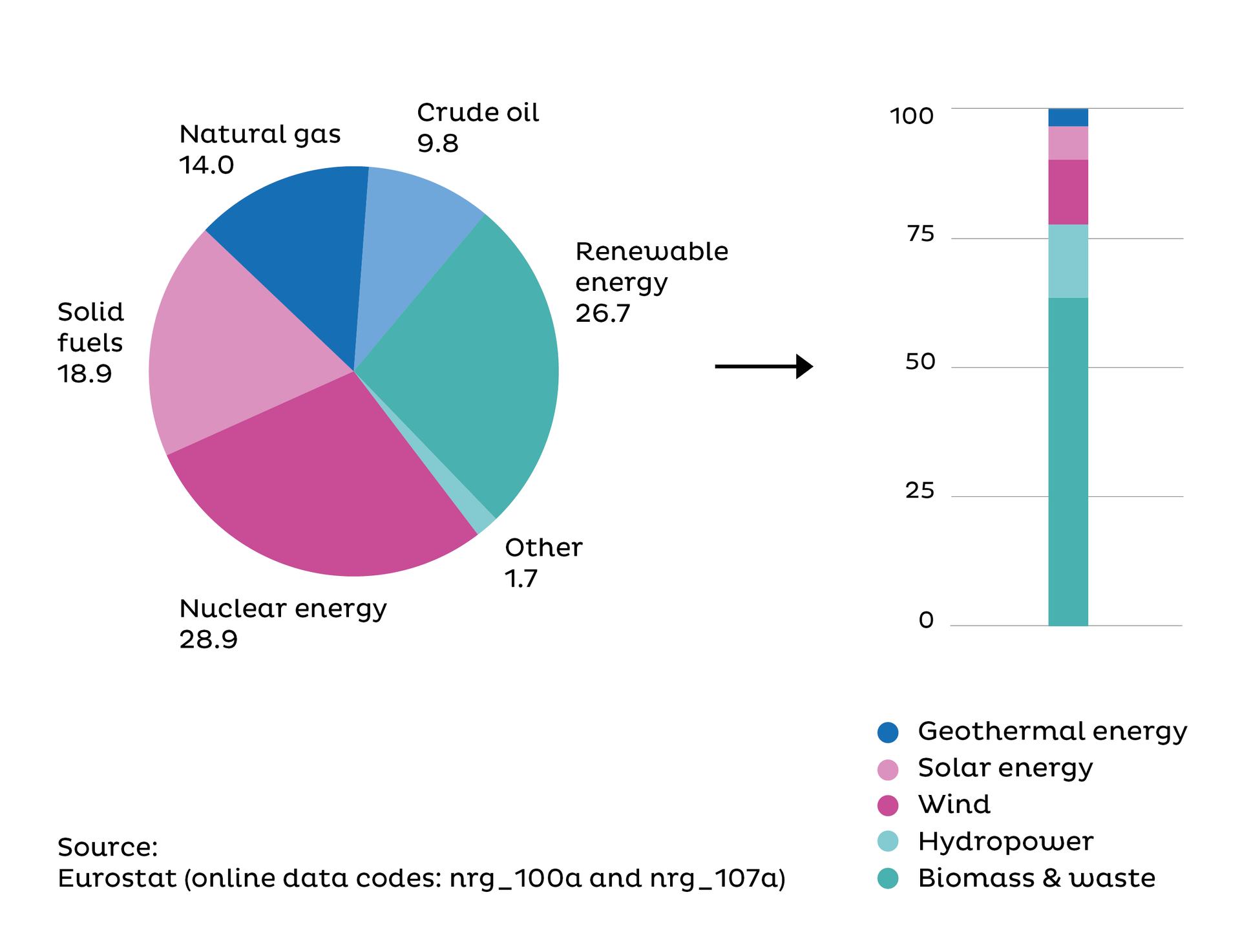

Share of natural gas in the production of primary energy in the EU-28, 2015

Source: Eurostat

EU Interests

As for climate change, the key EU targets for 2020 are a 20% cut in greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990, 20% of total energy consumption coming from renewable energy, a 20% increase in energy efficiency, and for 2040, an at least 40% cut in greenhouse gas emissions, at least 27% of total energy consumption coming from renewable energy, and an at least 27% increase in energy efficiency. These numbers have become hugely important as climate change became one of the drivers of energy management. Consequently, the European Commission came out with an EU Adaptation Strategy with the aim to have Member States adopt national plans to cope with the inevitable impacts of climate change by 2017. Some of the Member States have already done so.

The EU’s future energy supply is quite controversial. On the one hand, the decision to create a low-carbon economy necessitates cuts in the use of coal and other fossil fuels. On the other hand, the expansion and reasonable public mistrust towards nuclear fuels prevents it from becoming a substitute to fossil fuels. With these factors—as well as current international relations—in mind, the EU has introduced its Energy Roadmap 2050. According to it, the share of nuclear power in primary energy consumption will not undergo major changes before 2050, but the share of renewables and natural gas will. These long-term goals are more or less in accordance with the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

Thus, if the EU does not want to use oil and coal (both have been losing significance for decades), build more nuclear power plants, and, based on the state of technology, is not ready to supply its economy with renewables only, what can be used in the next few decades?

The answer is natural gas, of course, because the EU does not have any other choice. This resource will definitely play a key role in the transition in the short and medium term—which means until at least 2030 or 2035. Having the appropriate technologies, we know the accompanying emission values and that gas has the lowest environmental impact amongst fossil fuels. To find a solution to making it usable in the long run, the EU and further institutions have invested significant funds into the development of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technology. Carbon Capture and Storage is expected to be applied from around 2030 onwards. This choice makes sense but begs the question: Where will that gas come from?

The answer is a bit complicated. Firstly, technological advancements have made it possible for LNG (liquefied natural gas which has been converted into liquid form) to be stored and transported with ease even from Egypt. Secondly, the amount of natural gas necessary is going to change. Although its importance in the EU Member States’ energy mix will increase, the energy consumption of the EU has been decreasing in the last ten years, due to energy efficiency measures. These mainly concern the residential sector, expected to cause a 25% drop until 2030. The natural gas production of EU-28 fell by 9.3% from 2014 to 2015. The main reason is the natural aging of fields in the North Sea and production limits at the Dutch Groningen field, the biggest in Europe.

However, being ‘green’ is not just a choice for the EU, it is also a necessity. The lack of cheap fossil resources forces states to import them (mainly gas), which in turn makes the Union vulnerable to changes in the political and diplomatic climate. In case of gas, the main outside factor is Russia.

Speaking of Russia

Russia’s energy mix is 89% made up of fossil fuels, which means a 53% share for natural gas. Beyond its own needs, Russia possesses reserves of these resources so large that oil and natural gas exports accounted for 43% of Russia's federal budget revenues in 2015.

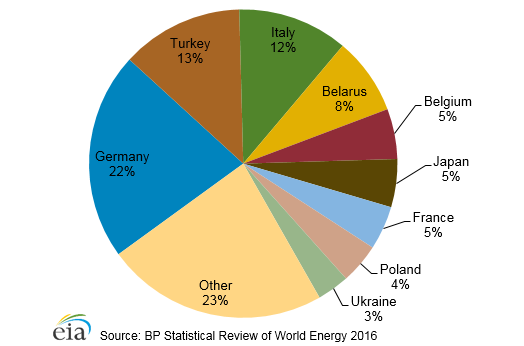

In the same year, the EU imported almost 30% of its crude oil and more than 30% of its natural gas from Russia. On the other side, almost 60% of Russia's crude oil exports and more than 75% of Russia's natural gas exports went to Europe. These numbers explain why Russia and Europe are interdependent in terms of energy.

Distribution of Russia’s natural gas exports by destination (2015)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (June 2017).

Following the Russian Military Intervention in Ukraine, in 2014 the United States and the European Union imposed a series of sanctions on Russia, hindering its economy by, among others, restricting access to U.S. capital markets, deepwater technology, and limiting export to Russia etc. One of the consequences was that virtually all involvement in arctic offshore and shale projects by Western companies ceased. These resources are unlikely to be developed without the help of western companies like ExxonMobil, Eni, Statoil, and the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC). As a short-term effect, all large-scale investments with western companies were halted, but no further damage was made, since these technologies would not begin to produce oil until 5 to 10 years later. Independently of this, the price of oil fell by more than half, causing the state deficit to grow and the government to raise the taxes on oil and gas companies and related activities. As a further consequence, the government collected double dividends than it normally did, and sold some of its share in the oil company Bashneft.

Looking for a Way Out

As conventional gas production declines, the European Union will have to rely on significant gas imports in addition to domestic natural gas production and, potentially, indigenous shale gas exploitation. The EU is interested in diversifying its energy mix, as well as its supply of imported natural gas. The energy strategy of the EU, particularly the extension of renewables, will likely intensify the need for natural gas as a dispatchable resource.

Around 2030, technical solutions concerning shale gas and CCS may change gas prices and competitiveness. As the aforementioned events and numbers suggest, Russia’s reserves will ensure its natural gas exporting ability in the next few decades; however, the EU is already seeking alternate supply routes. Our next article looks at its options.

Opening pic source: Shutterstock