Kategória: Research Blog

Forrás: https://digitalistudastar.ajtk.hu/en/research-blog/has-mediterranean-migration-been-diminishing

Has Mediterranean Migration Been Diminishing?

Impacts and Prospects of Italy's New Code of Conduct and the Libyan Provisions/Restrictions

Szerző: Bianka Restás,

Megjelenés: 10/2017

Reading time: 12 minutes

Two major factors have affected the “popularity” of the Mediterranean migration route this year. On one hand, the requirements of the new code of conduct adopted by the Italian government in July, and on the other, the increasing cooperation with the Libyan government and the new provisions introduced by Libya concerning the SAR area. Due to the complementary and mutually reinforcing effects of these two, the number of arrivals from Libya to Italy through the Mediterranean route has decreased notably recently. To evaluate the efficiency of the new code of conduct and the Libyan restrictions, we should take a closer look at the recent trends.

During the course of April 2016, the Italian media discussed on a daily basis that, as a result of the closure of the Western Balkans migration route and the refugee agreement between the European Union and Turkey (concluded on 18 March), Italy, as a frontline country, will play a key role in the management of the refugee crisis again. As a matter of fact, the importance of the Mediterranean migration route truly seemed to become more and more relevant: as it was previously expected, in May and June, the Italian migrant reception system was facing a significant pressure, and its management was becoming more and more challenging for the responsible bodies. The humanitarian aspect has also been put on the agenda due to those tragic incidents when ships carrying refugees were not able to reach the Italian coasts, and a large number of people on board drowned.

Rescue operations in the framework of the Triton mission

Source: Flickr, created by: Irish Defence Forces, licence: CC BY 2.0

In August 2017, 81 percent less potential asylum seekers* arrived to the Italian coasts compared with the same period last year. This July, the number of arrivals was lower by 66 percent than last July, said Dimitris Avramopoulos, European Commissioner for Migration, Home Affairs and Citizenship.

In the background of the decreasing numbers, the code of conduct adopted by the Italian government in July plays a crucial role. Its aim is to control and make the activity of those various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) more transparent that are carrying out humanitarian and rescue operations on the Mediterranean Sea.

The thirteen-point code of conduct contains major provisions such as the financial screening of the humanitarian and non-governmental organizations and comprises several restrictions and bans on switching off the radar and positioning devices, sending light signals to communicate with ships departing from the Libyan coasts, entering Libyan territorial waters and transferring rescued migrants to other vessels. Furthermore, certain forms of behaviour that would hamper the Libyan Coast Guard’s activity are also banned. At the same time, Italian authorities will also control the technical suitability and the equipment of the vessels in accordance with the code of conduct. Additionally, the regulation allows police officers to board NGOs’ ships in order to identify and investigate human trafficking activity.

The purpose of the code is to increase the transparency of the operations and activities of certain non-governmental organisations such as Save the Children, Doctors Without Borders, Proactiva Open Arms, Migrant Offshore Aid Station (Moas), Sea Eye, Sea Watch, Jugend Rettet or SOS Méditerranée.

It was necessary to elaborate a comprehensive regulation, as some organisations were accused of direct communication and cooperation with human smuggling networks. Vessels carrying out humanitarian and rescue activities have sometimes indicated their location using light signalling devices, which hugely facilitated the activity of smugglers. At the same time, doubts have been raised on the financial and economic background of the organisations as well. The code was accepted by some NGOs (Save the Children, Moas, Proactiva Open Arms), while others (for example Doctors Without Borders and Jugend Rettet) rejected it. Doctors Without Borders clearly expressed its misgivings concerning the provisions of the code, as it considers any military presence during the rescue operations irreconcilable with its activity. According to Jugend Rettet, the code not only hampers the humanitarian activity and their work itself, questioning the effectiveness of their operations, but also raises security questions concerning the lives of the volunteers carrying out humanitarian and rescue assistance. With regards to the issue, Rob MacGillivray, operation director of Save the Children, said: “Our experienced team members on board are concerned that in this situation boats will either be turned back to Libya, or migrants will die before they leave the newly extended Libyan SAR zone. People are crossing on flimsy rubber boats that take in water and don’t carry enough fuel.”

At the end of July, the Italian Government clearly stated that organizations, which would not sign the code, could not participate in the official humanitarian and rescue operations anymore, consequently, the number of active NGOs on the Mediterranean Sea has decreased with the adoption of the code itself. The new restrictions introduced by Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA), led by Fayez al-Sarraj, which modify the borders of the sea rescue area, the so-called SAR (search and rescue) zone,** have further reinforced this tendency.

What makes this limitation important is the fact that following the decision, the NGOs are no longer allowed to perform rescue operations within this zone. In other words, Libya has basically excluded the vessels carrying out rescue activities from the territory belonging to its scope of authority. The data reported by the Italian media about the exact range of the extended SAR zone were not consistent. According to the news published on 10 August, the Libyan authorities have the intention to increase their SAR zone from 12 nautical miles up to 97 nautical miles from their shoreline in the future. On 13 August, Save the Children emphasized that the SAR zone would be extended to 70 nautical miles by the Libyan authorities. As a result of the announcement, both Doctors Without Borders and See Eye suspended their activities. Later, Save the Children joined them as well, expressing its doubts on the future effectiveness of the rescue operations and the security guarantee of the rescue staff and the saved refugees, respectively.

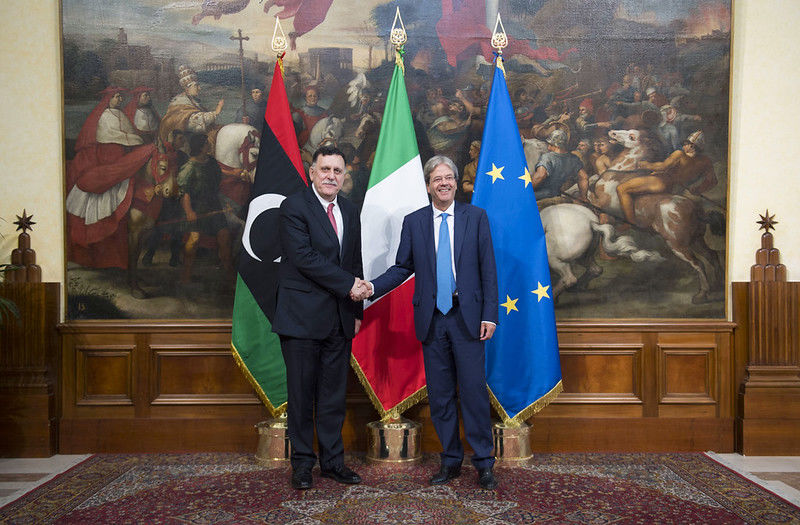

With regards to the issue, it is important to emphasize that the Italian government has become increasingly committed to the cooperation with Libya’s GNA. In February 2017, an agreement between the two countries has been elaborated with the aim to intensify their cooperation for the further stabilization of Libya, as well as to fight against smuggling networks and irregular migration. In the agreement, the two countries made commitments in several areas, highlighting the intention to strengthen the Libyan institutional structure and the Libyan Coast Guard as well. In accordance with the agreement, Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni emphasized that, beside the Italian and Libyan commitment, the role of the European Union is also indispensable through financial contribution, among others. Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj added that the strengthening of stability in Libya is crucial to overcome the challenges, while the country also needs a proactive engagement and support from Italy. At the end of July, it has been announced by the Italian government that Italy would support the Libyan Coast Guard with two military ships (providing logistical and technical assistance) in an effort to deter illegal migration and human smuggling into Europe.

Fayez al-Sarraj Libyan Prime Minister and Paolo Gentiloni at the Chigi Palace

Source: Flickr, created by Palazzo Chigi, license: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

According to the data of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), between 1 January and 31 August 2017, 99,127 migrants and potential asylum seekers arrived to the South-Italian coasts on the Mediterranean Sea. This figure represents a 14% decrease compared to last year’s data (115,068). Taking a closer look at the figures of July last year, a major decline can be observed: 23,600 migrants arrived to the Italian coasts in 2016, while 11,500 in the same month this year. At the same time, UNHCR mentions that 25,675 people arrived through the Mediterranean route in August 2016, while 8,546 people arrived during the same period in 2017, which is a significant decrease.

To illustrate the trends, it is worth examining the numbers reported by the International Organization for Migration (IOM): in 2014, 170,100, in 2015, 153,842 and in 2016, 181,436 migrants and potential asylum seekers arrived through the Mediterranean route to the Southwest coasts of Italy.

The complementary and mutually reinforcing effects of the current Italian regulation and the recent Libyan provisions clearly contribute to the decline in the number of migrants arriving to the Italian coasts. It is, of course, not the only reason for the changing tendency, as it has a lot to do with a wide range of challenges (like wars, ethnical conflicts, economic problems, changing weather conditions and others factors) in the Middle East, North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. It is worth mentioning that the presence of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria in the recent years has clearly influenced the number of refugees arriving in Europe. It is obvious that the losses that afflict the organization have a serious impact on the number of future asylum seekers.

It is difficult to predict how high this number will be by the end of 2017, but we can see that until 20 September, 102,887 migrants arrived in Italy through the Mediterranean Sea. However, it cannot be doubted that in July and August, the numbers have significantly decreased compared to last year. At the same time, we should remember that the problem does not seem to be solved in any way by the fact that asylum seekers do not reach Europe’s coasts. Although we can see significant changes in their location and distribution, the “destiny” of asylum seekers is practically in the hands of the Libyan authorities. One of the most important factors influencing the issue is how Italy, the European Union and the international community will support Libya in the future in its further stabilization and growth. It is indispensable that Libya as a transit country should become more stable and independent, while also being able to control its borders and combat human trafficking.

* It is not defined in the declaration how high the proportion of “forced migrants” (motivated by economic reasons) and potential asylum seekers (who are entitled to refugee status, temporary or subsidiary protection according to the 1951 Refugee Convention) is among migrants arriving through the Mediterranean Sea. In this article, I refer mainly as “migrants and potential asylum seekers” to the people coming to Europe via the Mediterranean Sea, because in many cases statistics do not separate the different legal terms.

** SAR (search and rescue) zone is a definition that can be linked to the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR). The 1979 Convention, adopted at a Conference in Hamburg, was aimed at developing an international SAR plan, so that, no matter where an accident occurs, the rescue of persons in distress at sea will be coordinated by a SAR organization and, when necessary, by cooperation between neighbouring SAR organizations. Parties are encouraged to enter into SAR agreements with neighbouring States involving the establishment of SAR regions, the pooling of facilities, establishment of common procedures, training and liaison visits.