Kategória: Research Blog

Forrás: https://digitalistudastar.ajtk.hu/en/research-blog/europe-s-dark-cloud

Europe's Dark Cloud

Szerző: Félix Á Debrenti ,

Megjelenés: 09/2017

Reading time: 10 minutes

On 31 July 2017, after several years of intensive collaboration with EU member states, industrial actors, and environmental NGOs, the European Commission adopted an implementing act which can greatly influence the future path of the Hungarian electricity industry. With its strict regulation, the EU strives to play a leading role in reducing coal-based power generation, therefore, the act focuses on those Large Combustion Plants which pollute the most in the EU. These power plants are slowly but steadily losing ground not only on a European but on a global level, too.

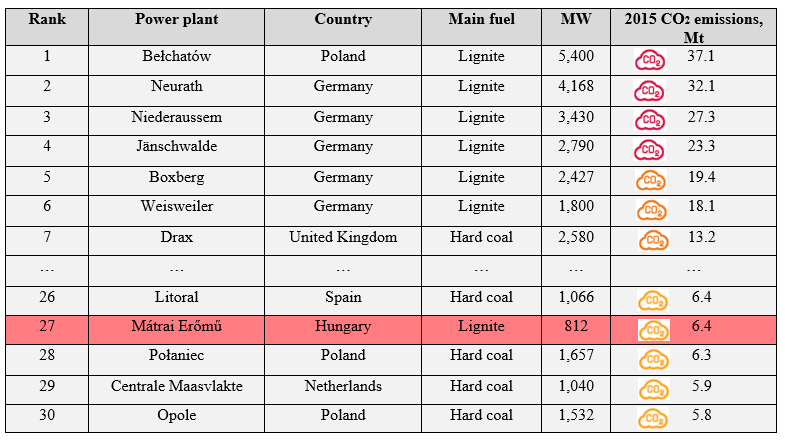

In Hungary, the facility most affected by the new act is the Mátra Power Plant, one of the most polluting facilities in the EU. The plant—which was built between 1965 and 1973—has five lignite units with a combined capacity of 884 MW and two gas-fired power generation units with a capacity of 33 MW each, producing 13% of the Hungarian electricity consumption. Based on the findings of Europe’s Dark Cloud 2016 study, the strategic Hungarian power plant emits 6.4 Mt carbon dioxide yearly, placing it 27th in the ranking of the most polluting facilities. The Polish (37 Mt) and German (32 Mt) power plants top the list with emissions that almost equal the annual Hungarian carbon dioxide emission. It is also worth mentioning that three countries alone are home to 19 of the ‘Dirty 30’ plants: Germany, Poland, and the United Kingdom.

The Mátra Power Plant among the ‘Dirty 30’

Source: CAN–HEAL–Sandbag–WWF: Europe’s Dark Cloud

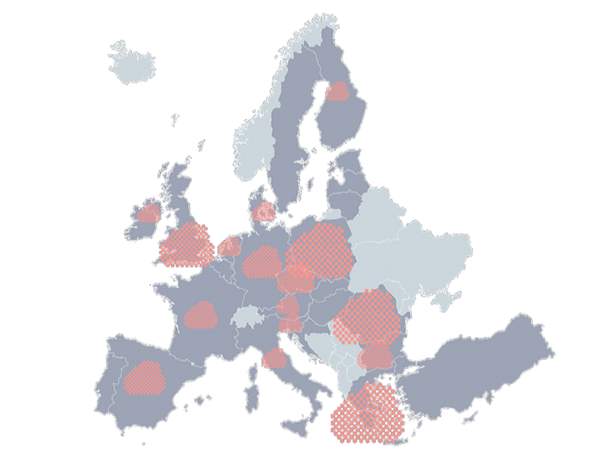

With the new regulations, affected power plants have four years to meet the prescribed criteria with heavy investments or retire the polluting units. Coal-related air pollution is a leading environmental cause of more than 23.000 premature deaths in the European Union, therefore, the main purpose of the Commission’s intervention is to speed up the renewable energy transition on the market. In Hungary, coal-related air pollution costs more than a thousand lives every year, 7 hundred of which are caused by the fine dust (PM2.5) from the Central and Eastern European region. The so-called dark cloud can be found all over Europe, but with varying density. The most critical levels are in Poland, Germany, the United Kingdom, Romania, and Bulgaria; these three countries make up three quarters of premature deaths in the EU.

PM2.5 pollution from EU coal power plants

Source: Coal Map of Europe, licensz: CC BY 4.0

In 2000 and 2013, the Mátra Power Plant already made major investments in reducing sulphur and nitrogen dioxide pollution, but with the 2021 limits, its two oldest units, each having a 100 MW capacity, will surely retire in four years. The power plant has been planning a 500 MW lignite-based unit expansion for years and has the necessary permits but has to face a few major roadblocks to building them. On the one hand, the current owners have been postponing the plan’s implementation since 2010, and on the other hand, an eventual expansion would go against the statement by Eurelectric (Union of the Electricity Industry) from this April, in which the organization’s members agreed not to invest in new-build coal-fired power plants after 2020. António Mexia, president of the Eurelectric trade association, said: “The power sector is determined to lead the energy transition and back our commitment to the low-carbon economy with concrete action.” The only two member associations not to sign the statement were the ones from Poland and Greece, which means that the current owners of the Mátra Power Plant—majority owner Rheinisch-Westfälisches Elektrizitätswerk AG (RWE), the Magyar Villamos Művek (MVM, Hungarian Electricity Private Limited Company), and the Energie Baden-Württemberg AG (EnBW)—have no intention to expand the facility. The big question is how the power plant will manage the current situation while it is being sold by the German RWE and EnBW owners and who the new buyer will be.

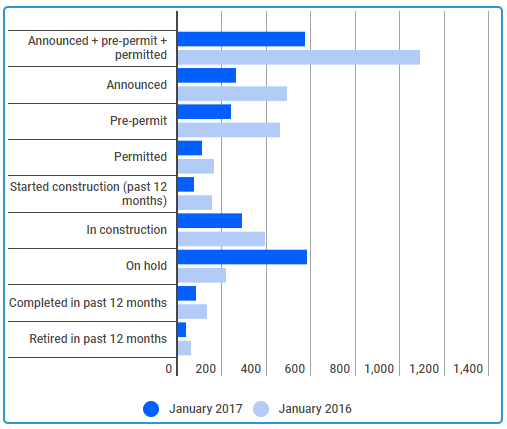

Coal-based power generation has declined heavily in the last few years in Europe and worldwide as well. Based on the study of CoalSwarm, Greenpeace USA and the Sierra Club, investments in coal plants reached their lowest level in 2016 due to policy shifts and the changing economic environment. The amount of planned coal power capacity in January 2017 was 570 GW, down from 1,090 GW a year earlier. With the decrease of coal-based power generation, the study does not exclude the possibility of reaching the 1.5 °C target set by the Paris Agreement, but also states that it would necessitate a more rapid retirement of currently operating units. In total, 64 GW of coal capacity was retired last year, mainly in the US and EU.

The amount of planned coal power capacity in 2016 and 2017

Source: The Guardian

Based on the data of Eurostat, in recent decades, the use of hard coal and lignite decreased steadily by almost the same amount. After 2013, this decrease was even more intense. In 2016, consumption of hard coal in the EU reached its lowest level at 239 Mt, 47.5 % less than in 1990.

Despite this decline, the 40% share of coal plants in global power generation is still considerable and essential. With the current trends, coal will keep losing its significance but will be able to dominate the market in the next decades. Meanwhile, policy shifts and changing economic environment will help to speed up the decarbonisation process.

Opening pic by Shutterstock.