Kategória: Research Blog

Forrás: https://digitalistudastar.ajtk.hu/en/research-blog/depleting-vital-resources-approaching-a-phosphorus-peak

Depleting vital resources

Approaching a phosphorus peak?

Szerző: Cecília Varsányi ,

Megjelenés: 05/2018

Reading time: 12 minutes

Nowadays, there are many of predictions stating that our Earth is running out of oil and other fossil fuels. However, the sustainable extraction of another vital element—phosphorus—failed to get into the focus of discussions until the last decade, even though its inventory is also facing depletion.

In 2010, after evaluating 41 raw materials based on their economic importance, risk of supply, and environmental impact, the European Commission adopted the list of the 14 most critical raw materials. Three years later, as a result of the latest analysis, the EU classified phosphorus, which is an essential additive of phosphate fertilizers, as a critical raw material as well—small wonder, as in Europe, 92% of the phosphorus supply is covered by imports. Along with this, the Commission has also issued a “Consultative Communication on Sustainable Use of Phosphorus,” which, besides the issue of the European phosphorus supply, highlighted the problem of phosphorus-related water and soil contamination originating from inadequate agriculture and sewage system management, too.

Phosphorus is quite a contradictory chemical element: because of its key role in energy storage, it is one of the most common components of living organisms, but at the same time, it is also one of the biggest enemies of surface watercourses, due to eutrophication and drastic water quality deterioration caused by phosphorus overload.

However, even though global stocks are relatively abundant, within the EU, reserves of phosphate-bearing rock are scarce (they can be found for example in Finland). Moreover, the volatility of the price of phosphate rock, which goes back to 2008 and the global financial crisis, has contributed significantly to an increase in fertilizer prices. Phosphorus is an irreplaceable component of modern agriculture: to our knowledge, there is no other material to replace it in forage and fertilizer. Thus, it is not surprising that about 90% of worldwide demand for rock phosphate comes from agriculture and food production. Consequently, even if demand could be decreased in its less important uses—e.g. in the industry where it is usually used for treating metal surfaces and in detergents—by replacing phosphorus with another raw material it would probably not significantly change the current high demand.

What about the reserves?

Information on the supply and demand of phosphate and phosphate-based fertilizers is quite limited, with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) cited as the most frequent reference. However, it also has to be mentioned that, between 1990 and 2010, USGS’ statistical databases were not fully updated with information from non-governmental sources. In 2010, based on sectoral information, the International Fertilizer Development Center (IFDC) reported new and far higher estimates of resources, and so USGS’ supply estimates were also reviewed in 2011.

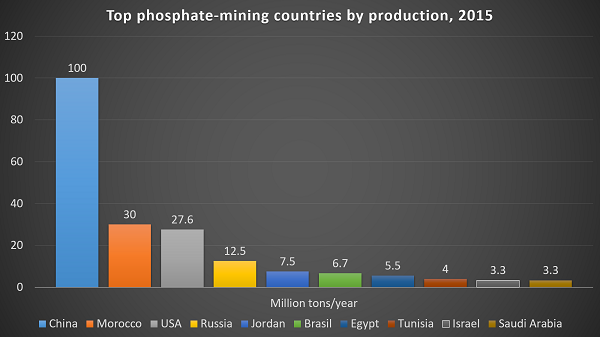

According to the available sources, the production of phosphate rock is currently concentrated in a few countries: Approximately 75% of the known and economically exploitable resources are owned by Morocco, which also makes it the world’s largest phosphate exporter. China and the United States also enjoy significant reserves, but most of the phosphate extracted in these two countries are not made available on the world market, posing further restrictions on the purchasing opportunities of other countries.

Top phosphate-mining countries by production

Source: USGS

Global demand for phosphate is projected to increase by 2.2% annually in the coming years, while the use of fertilizers will continue to grow as well: regarding the demand for phosphate-based fertilizers, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation (FAO) is forecasting a 58% growth in Asia, while 29% in the Americas, 9% in Europe, 4% in Africa, and 0.5 % in Oceania.

Like with most of the depleted resources, predicting the amount of phosphate stocks and whether they can meet demand in the long run is very difficult. One thing is certain, however: the high-quality and easy-to-exploit reserves are being used up.

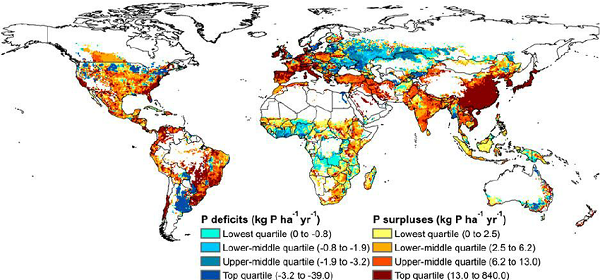

The global distribution of phosphorus used in agriculture

Source: Agronomic phosphorus imbalances across the world’s croplands, PNAS, 2011. Authors: Graham K. MacDonald et al.

Why should we strive to close the global phosphorus cycle?

Although the use of phosphorus-containing fertilizers and pesticides should be treated with extreme caution, in many cases fertilizers are not being used at the right time or in the right quantity. In the context of this general problem, a new study published in Water Resources Research shows that phosphorus load exceeded the assimilation capacity of freshwater bodies in almost 40% of Earth’s land surface. According to the same study, China contributed to 30% of the global freshwater phosphorus load, followed by India at 8% and the USA at 7%. This phosphorus pollution, however, does not only stem from agricultural activity, but also from domestic sewage and industrial activity. For Hungary, it is interesting to note that the Danube River Basin also ranks among the most severely polluted freshwater areas.

As the depletion of our high-quality phosphorus resources raises serious food safety concerns, phosphorus recycling technologies have been into the focus of technological research in developed countries. In 2008, there was a price spike on the global fertilizer market, experiencing an approximately tenfold increase, exceeding the $400-per-tonne price. In the following years, prices stagnated at a relatively high level of $100 per tonne, due to which the new business opportunity of recovering phosphorus started to attract several economic operators.

That being said, there are only a couple of initiatives that focus directly on phosphorus recovery. However, some exceptions can be mentioned. One such example is Sweden, where more than 50% of the phosphorus compounds in wastewater are recovered for fertilizer nutrient. In Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, we can also find wastewater treatment plants recycling the phosphorus content of wastewater. Fertilizer products based on phosphorus recovery from wastewater is becoming an emerging market overseas (mainly in Canada) and in Germany as well. In Berlin and Brandenburg, for example, the Berlin Waterworks (Berliner Wasserbetriebe, BWB), which supplies 3.7 million people with drinking water, has started to offer its own private-label brand agricultural nutrition product. Additionally, BWB contracted a retail organization to outsource the distribution and marketing communication of the phosphorus fertilizer product extracted from sewage sludge.

However, the application rate of (recycled) phosphorus in agricultural production should be calculated with sufficient caution, as soil phosphorus levels have been stabilizing in the Union’s arable lands—although these regions are still relying on the use of mineral phosphate fertilizers. For this reason, the calculation of nutrient intake and distribution before ploughing became mandatory in some countries. The distribution depends, among others, on the quality of soil, including the plant availability of nutrients.

Therefore, justifying the viability of a similar wastewater recycling investment requires a highly complex evaluation, and end-users’—i.e. farmers’—expectations on productivity, profitability, and environmental protection conditions need to be met without rebuke. In order to meet these requirements and to examine the both economically and environmentally acceptable options for European phosphorus supply, the European Sustainable Phosphorus Platform (ESPP) was created.

Although it is quite clear that we cannot expect a solution applicable to everything and everyone, it is worth considering what existing infrastructure we have and how we can build on it in the future.

Opening pic source: Shutterstock